A crippling strike by Islamist parties brought Pakistan to a standstill on Friday as thousands of people took to the streets and forced businesses to close to head off any change in the country’s blasphemy law ....

The general strike and protests Friday are an indication of the power Islamists hold on the streets of Pakistan. It is also a sharp contrast to the campaigns by rights activists and opponents of the blasphemy laws who have vented their opposition and discontent mostly on the Internet and social networks like Facebook and Twitter. Protest rallies by rights activists have been ineffective and relatively small.

... the huge show of force by religious parties, and even the attention local news media outlets gave them on Friday, would only embolden the religious elements in the country, analysts said. The dynamic was such that “the government may not be able to make any changes in the blasphemy laws in the coming years,” Mr. Rais predicted.

Friday, December 31, 2010

Rallies Defend Pakistan's Blasphemy Laws

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Qur'an written in Saddam Hussein's blood

The Guardian reports on the fate of a bizarre relic: a Qur'an written in Saddam Hussein's blood.

Over the course of two painstaking years in the late 1990s, Saddam Hussein had sat regularly with a nurse and an Islamic calligrapher; the former drawing 27 litres of his blood and the latter using it as a macabre ink to transcribe a Qur'an. But since the fall of Baghdad, almost eight years ago, it has stayed largely out of sight - locked away behind three vaulted doors. It is the one part of the ousted tyrant's legacy that Iraq has simply not known what to do with.

The article goes on to discuss how the Iraqi government is dealing with other monuments and relics of the dictators reign.

I suspect, though, that the Blood Qur'an will prove to be a unique problem for them. It combines in one relic an object of the most intense veneration for Muslims, the Qur'an, with a bodily substance closely identified with the deposed and executed dictator, his blood. Here the political pressure for its preservation and for its destruction will both be felt most fiercely.

Books have often functioned as relics of venerated figures that rival in importance their bodily relics. But in this case, the book IS a bodily relic.

LA Public Library's Photo Archives

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Boston Public Library's Photo Archive

and also images of the libraries and their patrons, like this of the Dorchester Branch's summer reading club:

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Iconic Manga

Along the way I stumbled upon the manga title Seinto oniisan, which usually gets translated into English as "Saint Young Men," but also carries "brotherly" connotations. The brothers in question are none other than Jesus and Buddha, who take a vacation from otherworldly life to shack up together in the Tokyo suburb, Nachikawa. They share a spartan, tatami-clad flat, wonder over new technology, do their own laundry (mostly jeans and t-shirts with various Buddhist and Christian references), visit amusement parks, get their food from the local 7-11, and celebrate Christmas and Shinto festivals.

continue reading at NYU's The Revealer

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

"Most Beautiful" Campus Libraries

Saturday, November 6, 2010

Launch of new scholarly society: SCRIPT

Its goal is to foster academic discourse about the social functions of books and texts that exceed their semantic meaning and interpretation, such as their display as cultural artifacts, their ritual use in religious and political ceremonies, their performance by recitation and theater, and their depiction in art. SCRIPT then incorporates the interests of the Iconic Books project, but also invites broader consideration of both iconic and performative dimensions of texts.

The society will sponsor programming at existing regional and international scholarly meetings and at colleges and universities. The first of these will be a concurrent meeting with the Eastern International Region of the AAR at Syracuse University, May 6-7, 2011 (see the Call for Papers).

We welcome new members and ideas for programs and venues to host them.

Friday, November 5, 2010

Who Needs a Library Anyway?

Who Needs a Library Anyway?

When then-President Gerhard Casper rhetorically asked this question, 12 October 1999 – as the title of his remarks at the dedication of the Bing Wing – there was much talk in the air about the imminent demise of libraries. Were these not a bunch of dinosaurs about to be smacked by the meteoric impact of the Web? Was the book not rapidly becoming an anachronism, a fetish object of a dying pulp-based culture? Many of us, with President Casper, disagreed with these glib notions then. But that was several generations ago, on the timescale of the information world around us. How have we fared since on the extinction short list?

Last month, forecaster and chair of our Advisory Council Paul Saffo delighted a select group of our donors with a talk about books, revolutions, and timescales. In a dense web of connected thoughts, he tied the great information revolution of the late 15th century to that of the late 20th, likening the titanic publisher-scholar Aldus Manutius to Steve Jobs, linking the once-revolutionary idea that a printed book is what it is (not a cheap knock-off of a proper manuscript) to the emerging identity of digital works as being something other than bad substitutes for physical books. He reminded us of an intrinsic life-cycle law of objects: things fade, or even disappear, after about a half-century, even (or particularly) Aldine editions or 1960s bestsellers. I am reminded that we avidly collect medieval “binding fragments,” i.e., pieces of manuscripts, mostly on vellum, that were cut up and recycled as stiffeners in bindings of later books, a practice we would now consider barbaric and wasteful (and very expensive). Apparently, after a century or so of European printing, manuscripts were considered expendable, rendered technically obsolescent by the printing press (and the scholarly efflorescence it made possible).

Universities and their libraries have been around for a fairly long time, say 700 or 800 years. The great university libraries that we are familiar with – those with millions of volumes addressing myriad subjects and disciplines – evolved through the vast post-war growth of academic research, coincidentally about a half-century ago. Are they – or, should I say, we – suffering decrepitude and irrelevance? I offer as evidence our experience with the New Graduate Student Orientation program last month, detailed later in this issue. It seems that Stanford’s new crop of grad students, arguably the most savvy and motivated class of information users alive, are quite aware they need libraries. Some of them may even need Aldine editions or binding fragments. All of them will use electronic resources on various sorts of devices. Whatever the form, the libraries will stand ready to help them obtain and use the stuff of scholarship.

Also past the half-century mark,

Andrew Herkovic

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Shea's The Phone Book

(h/t Rebecca Rego Barry on Fine Books & Collections)

America's Earliest Bibles

(h/t Sam Gruber)

Patronage and Sacred Books

The interest of this conference is twofold: the patronage of sacred texts in comparative contexts and the role of inter-religious elements in the production of sacred texts. The participants will address the adoption of book-making techniques across religious boundaries, Jewish/Christian/Muslim collaborative translations of art/text productions, interest in reading, producing, or interpreting the sacred texts of other religious traditions, and other related questions.

(h/t Claudia Rapp)

More Book Art

Alexander Korzer-Robinson has put a gallery of his sculptures made from books online here.

(h/t Andrew McTyre)

Monday, October 25, 2010

Desiring Books

Does the iconic value of the book keep us tied to this medium more than we should be? Is our move toward other ways of transmitting information being inhibited by our connection to the book as a representation of knowledge?My questions are: What are the stakes that people (and companies and universities and governments and religions) have in material books? And what are the stakes that people (and companies and universities and governments and religions) have in electronic texts?

Three Faiths at NYPL

First there was Torah, Bible, Coran: Livres de parole at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 2005, then Sacred at the British Library in 2007. Now there is Three Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, Islam at the New York Public Library. This series of exhibits comparing amazing manuscripts and printed books from each of the three Western religions represents a concerted effort to demonstrate what they have in common. "These exhibitions have a distinctive post-9/11 cast," observes Edward Rothstein in the New York Times.

The British exhibition even had the subtitle “Discover What We Share.” AndBut the exhibits and, especially, their online promotions linked above also demonstrate how libraries are using electronic media to publicize their treasures. In New York, images from the exhibit will even be projected on the side of a Fifth Avenue building . These electronic texts, far from obscuring the physical books, celebrate and revel in them. They broadcast their iconic, even monumental, status and draw crowds to see the material objects themselves.

in New York, too, the emphasis throughout is on commonality. At this historical

moment, this is meant to defend Islam against anticipated accusations.

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Scriptures in Three Dimensions

Monday, October 18, 2010

Report on Iconic Books Symposium

Saturday, October 9, 2010

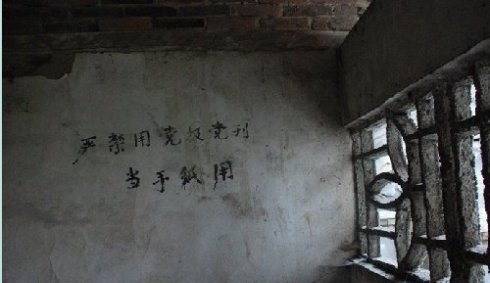

Toilets, papers, and writing

He translates: “Use of Party newspapers and magazines as toilet paper is strictly forbidden.”

And comments: "It is evident that some types of paper with writing on it are more precious than other kinds. In old China, one was not to wrap fish or wipe oneself with any paper that had writing on it, because writing itself was to be respected, no matter what the content or who the author was."

(h/t to Ayse Tuzlak)

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Privatization vs. "Sacred" Public Libraries

The reaction has been mostly led by patrons who say they cannot imagine Santa Clarita with libraries run for profit.Whatever one may think of Mr. Pezzasnite's business, he has described an overlooked phenomena. Why books and the libraries that contain them are regarded as "somehow ... sacred" is precisely what the Iconic Books Project tries to describe, on this blog, through our symposia, and in our publications...

“A library is the heart of the community,” said one opponent, Jane Hanson. “I’m in favor of private enterprise, but I can’t feel comfortable with what the city is doing here.”

... The suggestion that a library is different — and somehow off limits to the outsourcing fever — has been echoed wherever L.S.S.I. has gone.

... “Public libraries invoke images of our freedom to learn, a cornerstone of our democracy,” Deanna Hanashiro, a retired teacher, said at the most recent city council meeting.

NY Gentiles' inherited Mezuzahs

The doorways inside 30 Ocean Parkway, an Art Deco building in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn, are studded with mezuzas of all sizes and styles: plastic, pewter, simple, gaudy, elegant.

The people behind those doors are an assortment, too: Catholics, Baptists, Episcopalians, Buddhists, atheists and even a few observing the High Holy Days this week.

... Jews have left their mark on every aspect of New York life, but perhaps none are so ubiquitous and tangible as the palm-length encasements attached to countless doorways. So in a city that both savors history and likes to shake things up, it is perhaps inevitable that many of those mezuzas now belong to gentiles.

Left behind when Jewish residents died or moved out, they have survived apartment turnovers, renovations, co-op conversions, paint jobs and other changes wrought by time.

... Jews leaving a home are expected to leave the mezuzas behind if they believe the next residents will also be Jewish. If not, they must take the mezuza with them, to guard against the possibility that a non-Jew might desecrate it, knowingly or not. If a mezuza becomes too weathered, dirty or otherwise damaged, it is to be buried, as are all sacred documents, a service that a rabbi or synagogue can facilitate.

Non-Jews, naturally, are not bound by these customs, but many follow them out of deference. Alex Cohen of Borough Park, Brooklyn, who sells, installs and inspects mezuzas under the business name Mezuzah Man, said he had answered calls from non-Jews asking him to remove their mezuzas. The mezuzas should be handled respectfully, he said: “You don’t just put it in the garbage.”

But many gentiles choose to keep their piece of Judaica in place. “It’s good karma, if I can mix my religious metaphors,” said Brian Hallas .... The prospect of such a paint scar is what kept Eleanor Rodgers from removing the mezuza from the doorway of her home on Albemarle Road in Brooklyn, in a heavily Jewish neighborhood. “We’re not only not Jewish, we dislike organized religion,” said Mrs. Rodgers, a doctor’s receptionist who grew up in Ireland.

... But the idea does not sit right with some observant Jews who see the mezuza as an important emblem of Jewish identity. “To me, it’s very offensive,” said Sara Sloan, a retired schoolteacher in Windsor Terrace. “It’s taking my custom.”

... Still, Connie Peirce, 87, a retired secretary and Catholic who lives in Peter Cooper Village in Manhattan, said she often wished she had inherited a mezuza like many of her non-Jewish neighbors did. The tradition recalled her youth, she said, when her local priest appeared each Easter to write “God bless this house” on her family’s front door.

To her delight, one of her Jewish neighbors recently hung a mezuza on her doorway. “Every time I come home and remember, I kiss it and touch it and then I bless myself, saying, ‘In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, Amen.’ ”

OED online only

The second edition weighs in at a hundred and thirty-five pounds—about as much as the average woman—and fills four feet of shelf space. Weight and size are central to the idea of what the O.E.D. is; authority, in dictionaries, seems to come proportionate to mass, and when it comes to dictionaries, the O.E.D.’s authority is supreme. I have a sense that a weightless O.E.D., instead of being the last word in words, would become just more “information” of the sort that’s found everywhere online.

... I can’t help but feel that if the printed O.E.D. were to disappear, our language would suddenly feel a little less important. We won’t be able to look at its twenty volumes on our shelves and see just how impressive a thing a language is. Random browsing might become less common, and words might fall out of use as a result. Though serendipity remains possible online, it will be a sad day when we no longer have the joy of stumbling by chance on an exotic, beautiful, and exactly perfect word by opening randomly to one of the O.E.D.’s twenty-two thousand pages.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Illuminated Arabic Manuscripts in Munich

Monday, September 13, 2010

Virtual Book Burning and Its Consequences

... the Gainesville event might be the final culmination of the age of hijackers, where a small group’s manipulation of a powerful vehicle has far-reaching disastrous effects. Only in this case, the vehicle is the Qur’an, not an airplane. And the manipulation need only be virtual. Never has book burning been so effective without even occurring. Symbolic actions on the internet and their consequences in the real world now occur almost simultaneously. And the threat of a symbolic gesture and an actual one become one and the same.

Let me go even one step further. One could even say that the suggestion of book-burning is the only possible form of effective action today—far more effective than the book burning itself. In the twenty-first century it is virtually impossible (pun intended) to destroy books as a way of entirely eradicating a class of information, as Diocletian and many other emperors wanted to do. This is impossible to do because books are no longer physical objects but also electronic ones. It is also impossible to do because even electronic destruction may not be effective. At best, no matter how widespread a computer virus (a contemporary version of book-burning), there is no guarantee that such destruction would be complete.

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Threats to Burn Qur'ans

1. the power of scripture desecration, or talk about it, to focus media attention and therefore political discourse;

2. the difficulties that religious and political authorities have in controlling such talk and actions (in this case, the threat of desecration was diverted, but only after extraordinarily unified efforts by political and religious leaders of all kinds);

3. the degree to which mass publication of scriptures has placed the means for such acts in many people's hands;

4. the mass media's amplification of the effects of scripture desecration.

The chief difference between last week's news and previous reportage about desecrated Qur'ans is that this time, the news was generated by threats to burn them at a future time. Whereas the strict anti-blasphemy laws of countries such as Pakistan and Israel make charges of past scripture desecration potent weapons of political or personal conflict, American legal protections of free-speech allow threats of future scripture desecrations to polarize public opinion.

With that addendum, the story unfortunately shows again that “the prevalence of modern news media means that iconic scriptures provide convenient tools for both giving offense and taking offense, and today’s politics give many people reasons to do both” (Watts 2009).

The draw-backs of e-newspapers

Monday, September 6, 2010

Reading Media Wars Hit Home

Couples find themselves torn over the “right way” to read. At bedtime, a couple might sit side-by-side, one turning pages by lamplight and the other reading Caecilia font in E Ink on a Kindle or backlighted by the illuminated LCD screen of an iPad, each quietly judgmental.

Although there are no statistics on how widespread the battles are, the publishing industry is paying close attention, trying to figure out how to market books to households that read in different ways.

A few publishers and bookstores are testing the bundling of print books with e-books at a discount. Barnes & Noble started offering bundles in June at about 50 stores and plans to expand the program in the fall.

The quotations that follow provide ample examples of the rhetoric that has become standard in the debate over e-readers, contrasting the "look-and-feel" of books to the presumed inevitability of the digital revolution.

The Place of Reading in American History

A Bloody Relic Book

begins with three pages, each painted black, on which large drops of blood trickle down. The third page has been thoroughly worn. I am not absolutely certain this is the result of kissing, and part of it has been rubbed and smudged rather than merely kissed, but I think it very well could have been partially erased by kissing.

[A few pages later] the pages turn blood red, and thick gouts of blood pour down them from innumerable wounds. This disturbing decoration continues for ten consecutive pages (the last folio was cut out at some date, leaving only a stub). I count approximately 540 wounds on the bloodiest page, so perhaps taken together they were intended to represent the 5400 or more wounds received by Christ according to texts of late medieval devotion.

There are two openings like this before one reaches a third with two further woodcuts pasted in. The first represents a Man of Sorrows surrounded by twenty small compartments with instruments of the passion. Facing it is a larger woodcut of the five wounds of Christ with a heart at the centre over a cross. The left image (think back to the miniature in Harley 2985) carries an indulgence (later defaced): ‘To all them that devoutly say five Pater nosters, five Aves, and a Creed afore such a figure are granted 32,755 years of pardon.’

Lowden notes that "The book that follows this extraordinary prefatory matter is mostly written not in black ink but in the brilliant red pigment used for the blood." Obviously, an extreme and vivid example of a relic text that fully justifies our comparing the uses of such texts with icons.

(h/t Seren Gates Amador)

Garden of decomposing books

The Jardin de la Conaissance (Garden of Knowledge), a library garden and art installation made of 40,000 books, is part of the 11th International Garden Festival in the Jardins des Métis in Quebec's Lower St. Lawrence region. The artists, Rodney LaTourelle and Thilo Folkerts, say that by "exposing these fragile and supposedly timeless cultural artifacts to the processes of decomposition... The garden becomes a sensual reading room; a library; an information platform; an invitation to a provocatively foreign realm of knowledge." At the end of the festival, the books will be composted and recycled.

For more, see Treehugger.com and Refordgardens.com.

(h/t Wendy Bousfield)

Friday, July 30, 2010

Topical Bibliography of Iconic Books Scholarship

It can be accessed here or by clicking on Bibliography at left and following the link to Topical Bibliography.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

The Death of Sacred Texts

1 Marianne Schleicher, "Accounts of a Dying Scroll: On Jewish Handling of Sacred Texts in Need of Restoration or Disposal"

2 Jonas Svensson, "Relating, Revering, and Removing: Muslim Views on the Use, Power, and Disposal of Divine Words"

3 Dorina Miller "Parmenter, A Fitting Ceremony: Christian Concerns for Bible Disposal"

4 D. Max Moerman, "The Death of the Dharma: Buddhist Sutra Burials in Early Medieval Japan"

5 Måns Broo, "Rites of Burial and Immersion: Hindu Ritual Practices on Disposing of Sacred Texts in Vrindavan"

6 Nalini Balbir, "Is a Manuscript an Object or a Living Being?: Jain Views on the Life and Use of Sacred Texts"

7 Kristina Myrvold, "Making the Scripture a Person: Reinventing Death Rituals of Guru Granth Sahib in Sikhism

8 James W. Watts, "Disposing of Non-Disposable Texts: Conclusions and Prospects for Further Study"

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Stewart on Book Art

Stewart notes that book art, or as he prefers to call it, "bookwork" calls attention to books' materiality:

It is one way of studying their material preconditions, and this in the absence of their function as conduits--a function absent and gone but not forgotten. For nonbooks serve to itemize the features of book-based textuality that may otherwise be subsumed and elided by the channels of tansmission.

And that is just the beginning of his analysis...

Moerman on the Lotus Sutra

What is the Lotus Sutra? The scripture itself provides one ready answer: The Lotus Sutra is a Buddha relic. Like a number of other early Mahayana sutras, the Lotus Sutra asserts an equivalence between a roll of scripture and a relic of the Buddha. Employing a new theory of embodiment, the Lotus Sutra replaces the Buddha's corporeal remains with his textual corpus. The material form of the Buddha's word, rather than the material remains of the Buddha's body, is recognized as the central object of veneration and, as such, is to be enshrined in a stupa, a reliquary previously reserved for the remains of a buddha.

Moerman charts the development of ritual practices in medieval Japanese Buddhism that involved creating elaborate copies of the sutra in order to bury them in stupas. Such practices were motivated by concern "with the postmortem salvation of both the religion and the religionist." Moerman draws the moral for scholars of religion:

... the texts themselves did not bear the communicative or pedagogical function usually attributed to scripture. Great care and expense went into the production of these texts .... Yet the texts were never to be recited, studie, or taught, or at least not for 5.67 billion years. The value of their production and use lay in their media as much as in their message .... the power of sacred texts lies not only in their words and ideas but also, as the Lotus Sutra insists, in their materiality and instrumentality.

Moerman revists much of the same material in his essay published in The Death of Sacred Texts: Ritual Disposal and Renovation of Texts in World Religions, edited by Kristina Myrvold(Ashgate, 2010, see summary here).

,

Stolow on Artscroll

... through their material properties ArtScroll books can be seen to possess forces that strcuture and constrain the ways they are stored, read, displayed, or otherwise used in their designated social settings. This agency, embedded in thematerial design of the books themselves, is hardly incidental to the centrality ArtScroll texts are said to enjoy, whether in everyday life situations or in the ways ArtScroll is publicly imagined, discussed, embraced, or even rejected. (146)This leads Stolow to draw some conclusions about religious books in today's rapidly changing book marketplace:

... books can be said to possess a material agency whereby, for example, a leather covering has the power to convey an affective charge through its signifiers of dignity, solemnity, and artisanal authenticity. Form this perspective, it would appear that the continued (and indeed growing) vitality of the market for printed books rests on a deeper set of cultural assumptions about what kinds of technologies and institutional frameworks are best suited to generate "authentic" religiosu experiences and to sustain the bonds of religious community. ... Far from being rendered obsolete as "old" media, today's printed books have been reinvented as viable means of exercising authority and securing legitimacy through the particular disciplines and habits and the connective tissues that constituteIt's a great read!

text-centered religious community." (178)

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Symposium Schedule

I hope to see many of you in Syracuse in October!

Thursday, July 1, 2010

Stephen Doyle's Book Art

Stephen Doyle is a graphic designer who has worked with Barnes & Noble, Martha Stewart, The New York Times, and Wired magazine, among others. (See his company's website here for more information.) More recently he started using books as his media, cutting up the pages, and reforming the paper into sculptures. The images here are Andre Malraux's "Man's Fate" (top), and "The Trial," using Franz Kafka's book.

"Felt and Wire" has a nice interview with him on this process. Especially interesting was this comment in response to the reason he uses books:

Books are where ideas come from. The book is such a great form. Before doing these works, I was making concrete casts of books. What interested me was, if you take all the information out, does the form still have any power?Somewhere along the line I started wondering, well, what does happen when you take the ideas out? So, I started taking out the binding and the pages and setting the words free. And I’ve been working from there.

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

A Newly Iconic Library

The Chronicle of Higher Education reports that Ohio State's newly completed library renovation pays attention to look and feel as much as utility.

Walk in the door and into the sunlit atrium and look up. You can't miss the central stacks tower, its skin ripped off and replaced with heavy-duty glass. The books inside beckon, and the people studying and milling around them are clearly visible.

... Not long ago, in the earlier, euphoric days of the Internet, college administrators could be heard questioning the role of the library as a physical place on the campus, especially when one could trawl an ocean of knowledge from the convenience of one's own dorm room or office. What's the point of a library building in an interconnected world?

Ohio State's $109-million library project, which renovated some 300,000 square feet of space constructed in pieces over the past 100 years, is about the strongest refutation of that point of view as any, reinforcing the role of the library as a central hub and place of connection. ...

"Clearly the university wanted to signal that knowledge generation, use, and application is a priority of the institution, and there is no better place than in the stature and status of the library," says Mike Sherman, vice provost for academic administration.

... The tower not only is a prominent structure on Ohio State's Oval, the campus's central lawn, but proved to be a fantastic asset to the renovation. Now clad in glass on the first six floors, the tower is a striking feature at the center of the building. Mr. Lee, from Acock Associates, says that the entrances to the building were intentionally designed with low ceilings, so that visitors could not help but look up and see the stack tower when they entered the atria."It was a conscious attempt to manipulate you by compressing you and then letting the space really open up," he says.

... Library renovations inevitably lead to greater use of the collections and more visits, and Ohio State's project is no different. The building attracted around 3,000 people daily before the renovation; now 12,000 people walk through the door each day.Here and there, the designers laid down clues to the intellectual mission of the building, including the "foundation stones," 49 brass plates set in the terrazzo floor, along with 45 panels etched into elevator doors. The plates and panels represent various forms of writing that have been developed over the past 5,000 years. You can walk around the building and find alphabets, syllabaries, and graphic systems representing a host of languages, including Cree and Aztec, the old Irish alphabet Ogham, musical notation for the African drum called a djembe, and even Tengwar, the elvish script invented by J.R.R. Tolkien.

The stack tower is probably the building's most important statement. Ms. Diedrichs says the glass box of the tower serves as a reminder of what the library is for. "It conveys that scholarship and serious study are an important part of a college education and are a central part of the college," she says.

Ms. Diedrichs works on the third floor and takes the stack-tower elevators up in the morning to see what students are doing and what books they are pulling off the shelves. Early one recent morning she had already seen about 20 books lined up in a book truck, ready for reshelving.

"We like to talk about how everything is digital, but it's not entirely," she says. The marriage of study spaces with a prominent place for print is "like being at the intellectual crossroads of our campus," she says. "Students say, 'I am reminded of why I am at the university.'"

Saturday, May 29, 2010

Argentine Book Tank

See the video on YouTube where it is clear that the sight of this book-clad vehicle raises curiosity and attracts attention.

See the video on YouTube where it is clear that the sight of this book-clad vehicle raises curiosity and attracts attention.Sunday, May 16, 2010

Russia is for Reading Books, Then and Now

The theme is an old one in Russian culture. Michael Lieberman on Book Patrol points out these posters from the Russian Revolution tauting reading as the path to social revolution. The images come from the New York Public Library's digital gallery, "Posters of the Russian Civil War, 1918-1922."

Ot mraka k svetu. Ot bitvy k knige. Ot goria k schast'iu. [Book with slogan: From darkness to light, from battle to book,...] (1917-1921)

Gramota - put' k kommunizmu. [Literacy is the road to communism.] (1920)

Kniga nichto inoe kak chelovek, govoriashchii publichno. [The book is nothing else than a publicly speaking person.] (1920).

Kniga nichto inoe kak chelovek, govoriashchii publichno. [The book is nothing else than a publicly speaking person.] (1920).

Friday, April 30, 2010

The Law Library at Yale University is displaying volumes from its rare book collection that have been bound using other texts as scrap material. The exhibit, "Reused, Rebound, Recovered: Medieval Manuscript Fragments in Law Book Bindings," includes these twelve small volumes of the Corpus iuris civilis, published in Lyons by Guillame Rouille in 1581, which have been neatly covered by pages from a biblical manuscript, ca. 1350-1450. For more pictures, see Nancy Matoon's discussion of the exhibit on Book Patrol.

This example shows that the relative iconicity of texts varies considerably in time and place, and not just in the contemporary rare book market.

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

From Web to Coffee Table

Saturday, April 24, 2010

The Shape of the Decalogue Tablets

Menachem Wecker in the Jewish Press surveys the shape of the Decalogue in Jewish art, especially late medieval illuminated manuscripts. Though the stereotypical round-topped double tablets appear in the Sarajevo Haggadah (right, ca. 1350), he also finds rectangles, single tablets, and framed texts. No standard shape or depiction carries the day, though Wecker observes that

the claim Jews envision the tablets in the rectangular while Christians hold them to have been rounded does not stand. For the most part, Jewish artists do seem to have followed the grammar of the biblical phrase luchot avanim (tablets of stone) or luchot ha'brit (tablets of the law), which is always presented in the plural, while many Christian artists attached the two tablets to each other.

Perhaps the most interesting depiction is in the Alba Bible (left). Wecker comments:

The tablets seem positioned to squash Moses' head, and if one examines them carefully, one notices that the text - which is not carved into the rock, but painted on top of it - sometimes overflows the allotted space and hangs midair, particularly in the third commandment. It is almost tempting to read the white space surrounding the letters as empty space, in which case the artist has interpreted the forms of the letters as all being miraculously suspended.

Relic Torah

... after The New York Times published an article about the Torah and the Maryland rabbi, Menachem Youlus, questions surfaced about how it came to be discovered.The significance of using a genuine Holocaust torah scroll was expressed by both the donor and the synagogue's rabbi:

As a result, David M. Rubenstein — a billionaire financier who had bought the Torah from Rabbi Youlus and donated it to Central Synagogue — sought to confirm the scroll’s authenticity. Mr. Rubinstein ... hired Michael Berenbaum, a Holocaust historian and former director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Holocaust Research Institute.

“What I found is the claim for the origin of the Torah could not be verified,” Dr. Berenbaum said last week.

... Dr. Berenbaum had him find a Torah “whose Holocaust provenance is not in question” — it was the one placed in the ark on Monday. That Torah had remained in the Romanian Jewish community through the Holocaust and was later taken to Israel.

Mr. Rubenstein said he had donated the Torah to Central Synagogue “so its congregants could have the sacred experience of reading Scripture from a scroll that had survived the Holocaust.”UPDATE:

“As one who has gone to the camps and assimilates into my being the horror of the Holocaust,” Rabbi Rubinstein said at the time, “this gives meaning to Jewish survival.”

The Washington Post reported on October 11, 2012, that Rabbi Menachem Youlus pleaded guilty and was convicted of selling fake Holocaust scrolls and defrauding investors.

Youlus, the self-proclaimed “Jewish Indiana Jones” ... spun cloak-and-dagger tales of “rescuing” sacred Torah scrolls lost during the Holocaust, but those tales were lies. ... Despite Youlus’s claims that he found holy relics at concentration camps, in monasteries and in mass graves, passport records show he never traveled to Europe. ... More than 50 of his purported Holocaust Torahs made their way to congregations in the Washington area and beyond. Synagogues held emotional ceremonies to rededicate the scrolls for worship — a symbolic show of Jewish triumph over Hitler.Youlus was sentenced to 51 months in prison and ordered to pay $990,366.05 in restitution.

Rising Prices for "Iconic Books"

the increasingly separate iconic and traditional rare book, manuscript and ephemera markets. They have been moving in diverging [directions] for some time. Great examples of rare and unique items have been selling for substantial prices while no less rare but less known and less coveted material has gone unsold or brought lower than expected prices. As the market has become increasingly transparent the many now see what the few have long known and it is changing what people buy and how much they pay. We are living through a time of significant change: the re-pricing of the market. The iconic category looks safe, pedestrian rarities risky, the in-between the subject of endless interpretation.He credits this separation to "increasing transparency and increasingly unified markets functioning in real [time]," with the result that "highly collectible material should continue to do well while lesser materials continue to leak value."

McKinney's definition of an "iconic book" as "highly collectible" overlaps considerably with this blogs use of the term. But we also draw attention to books that are commonplace yet revered and ritually privileged, like scriptures. My experience with last summer's garage sale shows, though, that iconicity makes even the most commonplace Bibles collectible.

(h/t David Stam)

Missing Covers

I think they'll have to do more than that, because the association between a book and its cover will be lost if readers don't see it every time they start to read.Among other changes heralded by the e-book era, digital editions are bumping book covers off the subway, the coffee table and the beach. That is a loss for publishers and authors, who enjoy some free advertising for their books in printed form ...

As publishers explore targeted advertising on Google and other search engines or social networking sites, they figure that a digital cover remains the best way to represent a book.

Meanwhile, monks that bind books to support their monasteries find the business falling off, reports the Catholic Sentinel. In this case, the culprit is the development of digital journal archives by university libraries. The Trappists of Our Lady of Guadalupe Abbey (Lafayette, OR) are

not completely losing accounts, but the amount of work sent in by customers has plummeted. During the 1980s, the monks bound about 50,000 books per year. By 2000, the number slid to 40,000 and now it stands at 23,000.

Bookshelf Wallpaper

Monday, March 29, 2010

The Digital Publishing Future?

Despite the all-digital-all-the-time form of Epstein's vision, he argues that physical books will remain necessary.

Digital content is fragile. The secure retention, therefore, of physical books safe from electronic meddlers, predators, and the hazards of electronic storage is essential. ... actual books printed and bound will continue to be the irreplaceable repository of our collective wisdom.His business model of decentralized digital publishing does not, however, explain how that will be financed.

At the end, he points to his stacks of books to show his allegiance to the material tome. But his entire piece emphasizes "the inevitability of digitization as an unimaginably powerful, but infinitely fragile, enhancement of the worldwide literacy on which we all—readers and nonreaders—depend."

But considering how unpredictable the short history of textual digitization has already been, who can say whether and in what regard he is right?

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

The Most Magnificent Book Store in the World

Book Patrol: The Most Magnificent Book Store in the World features El Atenea bookstore in Buenos Aires, inside an elaborate, 1919 theater.

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

Money for Preserving Books

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Why Books Matter

Worries about the future of books hit home recently on the campus where I work. The university library announced plans to dispose of some materials and move many more books to a commercial storage facility across the state in order to free space in the stacks for new acquisitions. These plans came soon after renovations transformed two of the library’s seven floors from book stacks into a coffee shop, a computer commons, “collaborative learning spaces” (i.e. tables with chairs), and classrooms. So the announcement of deacquisition and off-site storage plans prompted an uproar among humanities faculty members and students, producing 113 faculty signatures (including mine) on two letters of protest. Faculty in the sciences and social sciences soon circulated their own protest letters in solidarity with the humanists’ initiatives. A student petition against the plan garnered more than 1000 signatures. All demanded greater consultation and collaboration in developing library collections and policies. The library responded with its own letters and policy papers, claiming that it has always sought input, especially from faculty.

Beyond the argument over input on library practices, however, the dueling documents reveal a conceptual gap between the library’s administration and the protestors. Comparing the professors’ letters and the librarians’ policy papers shows that their subjects are completely different. The library’s policies focus on “information”—how and by whom it is accessed, distributed, analyzed and used. The faculty’s letters almost never mention that word; only the social scientists use it at all. The letters focus instead on the importance of reading physical books and documents, browsing stacks and viewing fold-out charts and maps. The library letters emphasize collaborative learning while the professors focus on the needs of solitary researchers. The library invokes utility while the faculty worry about recruitment and institutional prestige. The different subjects of the dueling documents show that this dispute involves very different ideas about books.

The whole affair could be dismissed as one more academic tempest in a teapot were it not for the much wider debates over the role of libraries on college campuses, over the state of book publishing and marketing, and, of course, over the future of books themselves. Like most long-standing social institutions, libraries are more than just mechanisms for providing particular services. They symbolize a cultural ideal. But libraries exemplify that ideal only by virtue of the books they house. Questions about the roles of libraries are, at bottom, questions about the significance of books.

Missing in this debate has been any exploration of the values that modern societies invest in books. As it happens, my university also hosts an interdisciplinary research program aimed at documenting and analyzing precisely this question across history and diverse cultures. I am co-founder of the Iconic Books Project, and so have followed the library debate with particular interest. It has prompted me to imagine how an iconic books perspective can help us understand the values attached to browsing stacks, material books, and library architecture.

The Importance of Browsing

Complaints against both digitized texts and off-site storage of library books frequently evoke the experience of browsing library shelves. Faculty members report the benefit of getting an overview of an entire subject contained in a collection. They repeat stories of finding just what they were looking for in the book next to the one they came into the stacks to collect. They celebrate how browsing stacks can produce random juxtapositions that neither cataloguing systems nor their own research plans anticipate, yet which provide the key to resolving their problem or to setting their research onto a new and more productive path. For them, this kind of browsing is not possible with either a catalog or an internet “browser” because its success depends on the physical juxtaposition of books on a shelf.

The open-stack library that makes browsing possible manifests an old idea. The notion that the contents of texts should be randomly accessible has slowly grown in strength over three thousand years. It decisively shapes the physical forms of books as well as libraries.

Ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian libraries were owned by temples and royal courts who strictly limited access to their priests and officials. When new religions made knowledge of their sacred texts public instead of keeping them secret, public reading and interpretation became a standard element in Jewish, Christian and Muslim worship. At first, the books were scrolls whose pages were sewn together edge to edge. Scrolls must be read sequentially, either the whole text at once or sections over a series of sessions. In synagogue services, Torah scrolls are still read sequentially over a year. The scroll form makes it hard to compare different parts of the same book, and it cannot be opened randomly.

Ancient Christians adopted a different technology for their sacred books, one that binds together sheets of parchment or paper on a single edge. This is called a codex and is the form that almost all books take today. The codex allows you to skip from one part of the book to another easily, to compare different sections, to read in any order that you want, and even to read randomly by letting the book fall open. People of various religious traditions still use random access to divine in scriptures a message appropriate to their circumstances.

The public library movement of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries made volumes of literature and information much more widely available, often in the form of open stacks libraries that allow the public to browse the shelves. Open stacks multiply the advantages of codex technology. You can access as many volumes as you can lay your hands on in any way you wish, including randomly. Open stacks represent the reader’s complete control over the physical process and sequence of reading. Refusing such access by storing volumes off-site or on-line feels like imposing the textual strait-jacket of a scroll on readers who have become used to the freedom of a codex.

Attention to the physical form of texts reminds us that reading is an embodied practice. You must hold a book physically, brace it with your hands or put in on a table, position your body in certain ways and, of course, focus your eyes in order to read. Working on computers or e-readers requires different physical activities that have provided much fodder to debates about e-books.

But here I want to point out that visiting a library is also an embodied practice. Walking into the building, navigating the stacks, sitting in carrels to study your finds, and checking out and carrying away the most promising books comprise physical routines that have long characterized the scholar’s lifestyle. The convenience of electronic texts and computerized catalog searches that deliver texts to you is offset by constricting the physical scope of your research activities to your own desk and computer. This loss may be felt especially keenly by faculty and students in the humanities whose research already tends to be the most individualistic of all the disciplines in the university and, therefore, the most isolating. For them, trips to the library have traditionally provided a physical research activity that many are sorry to see go.

Material Books and the Desire for Textual Permanence

Books represent more, however, than just the reader’s control over the reading process. They are powerful cultural symbols. Books matter because they are material manifestations of our culture’s ideals: educational ideals, political ideals, philosophical ideals, and religious ideals. They represent our best hopes for ourselves. But ideals can be hard to remember, much less live by. Books seem to preserve our values in physical objects. They are material manifestations of whatever we hold most dear. And when we struggle to know what that is, we can read books to remember what we’ve forgotten.

To a great degree, therefore, the cultural significance of books involves old knowledge. They represent our desire for old knowledge even while publishing new information. The publishing business, of course, wants new products to sell. Professors, especially those in the humanities, want to write and sell books. Research universities require them to do so. As a result, more books are published every year than the year before, and research libraries find themselves losing ground and floor-space in the effort to keep up. But unlike chain bookstores, libraries owe their cultural prestige to their role in preserving old books as much as in acquiring new ones.

Many fields of the humanities as well as qualitative fields in the social sciences promulgate old knowledge preserved in books. Of course, humanists also conduct creative research, use electronic resources and expect the most recent intellectual trends to appear on their library’s shelves. But their teaching tends to be book-centered and many of those books are old. In courses in literature, philosophy, history, and religion, students’ work consists mostly of reading books, often primary texts. Distinguishing primary from secondary sources is a hallmark of humanistic research that emphasizes the importance of reading authors from diverse times and cultures. Many professors in such classes teach book in hand, modeling by their own performance a text-centered way of thinking. Explicit in such performances is the assertion that these old texts still have important things to say to contemporary students. Implicit is the hope that, in this or another book, we may find forgotten wisdom that could benefit us and our society.

Such pedagogies reflect wider cultural commitments. Human cultures tend to vest some material objects with important, even transcendent, meanings. Objects like national flags, religious art, and grave markers evoke powerful emotions and motivate the behavior of very many people, no less today than in the past.

Books also evoke powerful emotions and symbolic connotations. That is most obviously the case for religious scriptures. The Torah, Bible and Qur’an, to name only three, function as icons not only for Jews, Christians and Muslims, but also serve as powerful symbols of those religions within the wider culture. But many other books also exhibit iconic qualities, if not to the same degree. The image of the book (codex) appears in art and other visual media to represent knowledge and learning. It is a conventional prop in the portraits of scholars and writers. Many universities put images of books on their institutional seals.

Material books evoke a semi-sacred sense in many people. They will therefore go to great lengths to avoid destroying them. Librarians, who must dispose of redundant or out-of-date volumes, have told me stories of loading the dumpster at night so as not to be seen. The cultural roots of this antipathy run deep. Memories of cultural loss because of mass book destructions lie at the roots of both Chinese and Western cultures: the first Quin emperor ordered the destruction of most forms of literature in 213 B.C.E, while Roman troops accidentally burned the library of Alexandria in 48 B.C.E. Historians debate the accuracy of both stories, but that has not lessened their cultural significance. Conflict between and within religious traditions has frequently included destroying books and attacking their owners. These were also prominent practices of totalitarian governments and political movements in the twentieth century. As a result, book burning remains one of the most outrageous activities in contemporary culture, closely followed by attempts to ban books from libraries or bookstores.

From a practical point of view, all of this is inexplicable. Books are very common and widely distributed commodities. The destruction of one copy or even many copies will not seriously threaten the availability of mass marketed books. But such practical observations do nothing to lessen the iconicity of books. Most religious scriptures are even more widely distributed, often in very inexpensive form, and so common that the destruction of tens of thousands of copies would not seriously affect access to their texts. Yet news of scripture desecrations arouses very strong fury and catches the attention of the world’s news media. The iconic status of books in contemporary culture is unaffected by their ubiquity or commercial value.

So research libraries in the early twenty-first century find themselves in a difficult predicament. On the one hand, the ever-rising number of academic publications and ever-expanding scope of scholarly interests puts enormous pressure on their acquisitions budgets and their shelf space. It is understandable that the advent of electronic texts might look like a timely technological fix to these woes. On the other hand, the broader society privileges research libraries—and the universities that support them—as conservators of intellectual culture. The prestige of a university is often crudely calculated by the sheer number of volumes in its collections. (Even more extreme examples of the social priority on book conservation can be found in national depository libraries like the U.S. Library of Congress and the British Library, which try to collect most if not all books published in their countries.)

E-books do not serve this desire to preserve culture in books very well. Electronic texts are an ephemeral textual medium, like chalk boards. And like chalk boards, preserving electronic texts depends on frequent copying, though they are much easier to reproduce. They show absolutely no promise for permanence, however, either physically (on various kinds of computer hardware all of which suffers rather rapid physical decline and even more rapid technological obsolescence) or culturally (due to ever-changing software that overwhelms the human expertise needed to operate old systems). The widespread hope that constant copying and upgrades will preserve e-texts long term shows remarkable ignorance of human history. When physical, economic, and political systems can all be disrupted on a catastrophic scale—as they were several times in the twentieth century alone—systems that depend on power and communication networks cannot be trusted as reliable long-term repositories of cultural memories.

The research university library has served the function of cultural repository for centuries. Though its collections can also be destroyed by war and other catastrophes, books at least do not require dedicated electrical technologies in order to work. They need only a human eye and a mind that understands the language and script they contain, and even that knowledge can often be reconstructed after being lost.

Books preserved in libraries of various kinds have proven to be the most reliable, flexible, and portable technology for long-term cultural preservation for the last two thousand years. That is why books symbolize the preservation of cultural ideals, and that gives them a lot of cultural prestige. Libraries that appear to abandon the role of book preservation lose the prestige that goes with it.

Architectural Values

On university and college campuses, library buildings share the culture’s symbolic investments in the books they contain. It is a very old religious idea that books of scripture convey some of their importance to the buildings that house them. A synagogue is holy because of the sacred Torah scrolls it contains, a Sikh gurdwara is a shrine for the Guru Granth Sahib, and a mosque is holy to many Muslims because of its Qur’ans. Buddhists as well as Christians have frequently treated books of scripture just like the relics of saints, and the boxes and buildings that contain them as reliquaries.

Library architecture often reflects this tradition by imitating Greek temples or Gothic churches. University professors and administrators frequently claim that the library is the heart and soul of the university, but university crests show that the real referents are the books inside those libraries.

This architecture and rhetoric do not make casual claims. They tie the university’s identity to material artifacts—books—that exemplify learning and wisdom, in contrast to other campus architecture—such as the football stadium—that emphasizes very different cultural values. Library policies therefore evoke heated debates because the cultural identity of universities in general, and the humanities in particular, are at stake. Books matter because they are the icons for such values. A university without a book-stuffed library is a university without a soul.

I hope that will not be the case at my university. Greater collaboration between faculty and librarians should result in more books on open stacks, and that will represent a tangible recommitment to the university’s role as a cultural conservator.

Besides, that investment will benefit the university’s research programs in another way: those books contain lots of interesting information too!

© 2009 James W. Watts