Writing in Christian Century, Heidi Haverkamp reports on her personal experience participating in hand-writing part of the Bible. The idea began in at the Abbey of St. Gall (which, btw, has a famously iconic library):

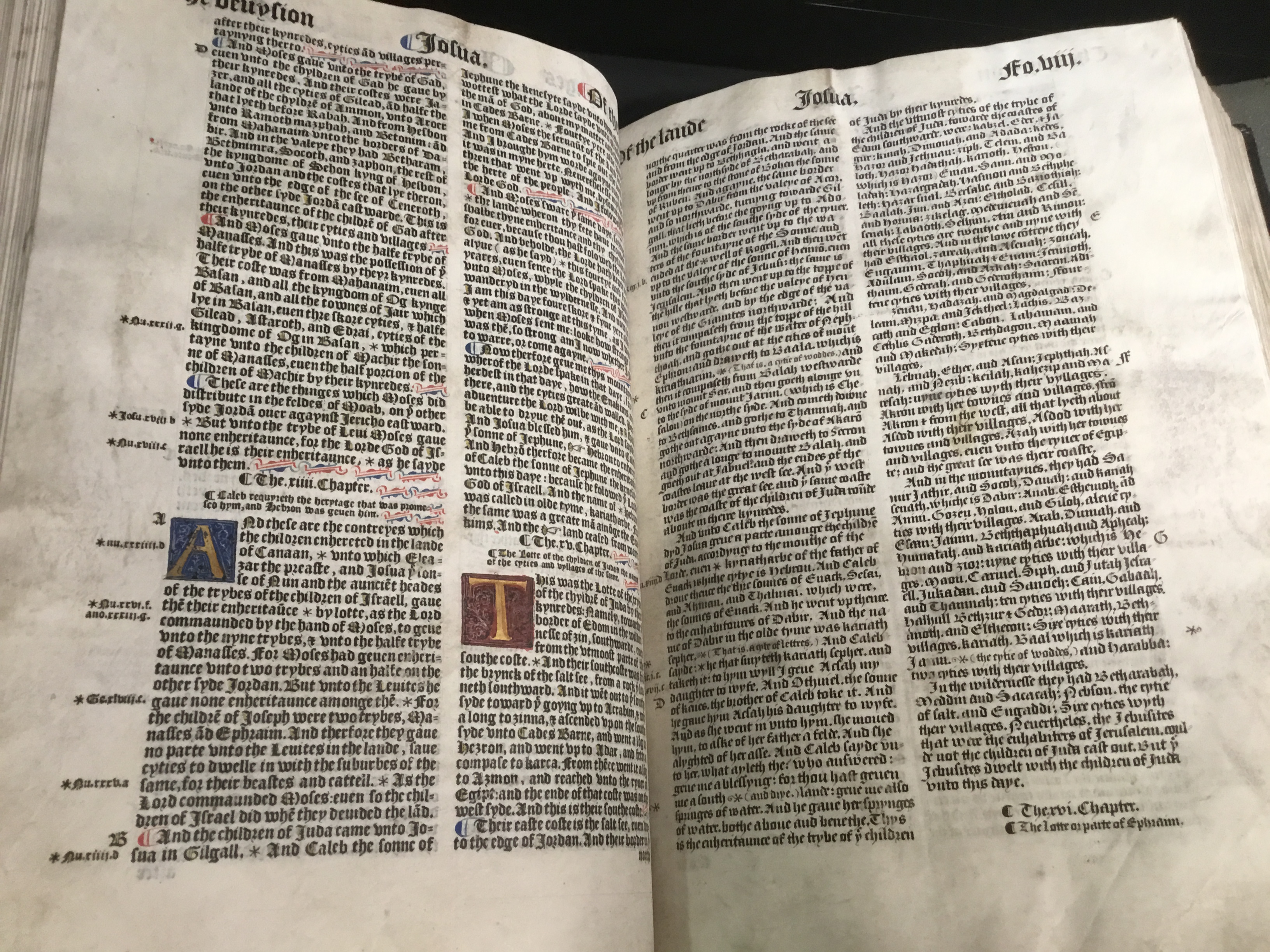

In the early days of quarantine, the Roman Catholic Abbey of St. Gall in northeastern Switzerland invited more than 1,000 parishioners to create a completely handwritten and

illustrated Corona-Bibel while they sheltered in place. The project inspired clergy in Chicago and Lincoln, Nebraska, to launch similar projects. While the American iterations are smaller in scope than the Swiss Corona-Bibel, focusing on select books of the Bible rather than all 66, the projects all share a common purpose: to gather people into community during a crisis and encourage them to experience the healing, comforting power of God’s word.

Haverkamp signed up to take part. She reports that

copying the text of Matthew made God’s Word sacramental in a new way. I had to pay attention to the text of the chapter as a whole, and it felt like I was reading with a part of my brain I have never used for Bible study before. The result was a deep and tangible immersion in scripture; I was inside each passage, not just looking on from a distance.

... Alone at my desk, I joined that vast spiritual family, the communion of saints, with Hebrew scribes, medieval monks, and kids and adults in Chicago and around the world, picking up our pens together.

This is a creative response to the isolation of the epidemic. But some European churches have sponsored and displayed bibles hand-written by the parishioners for some time.

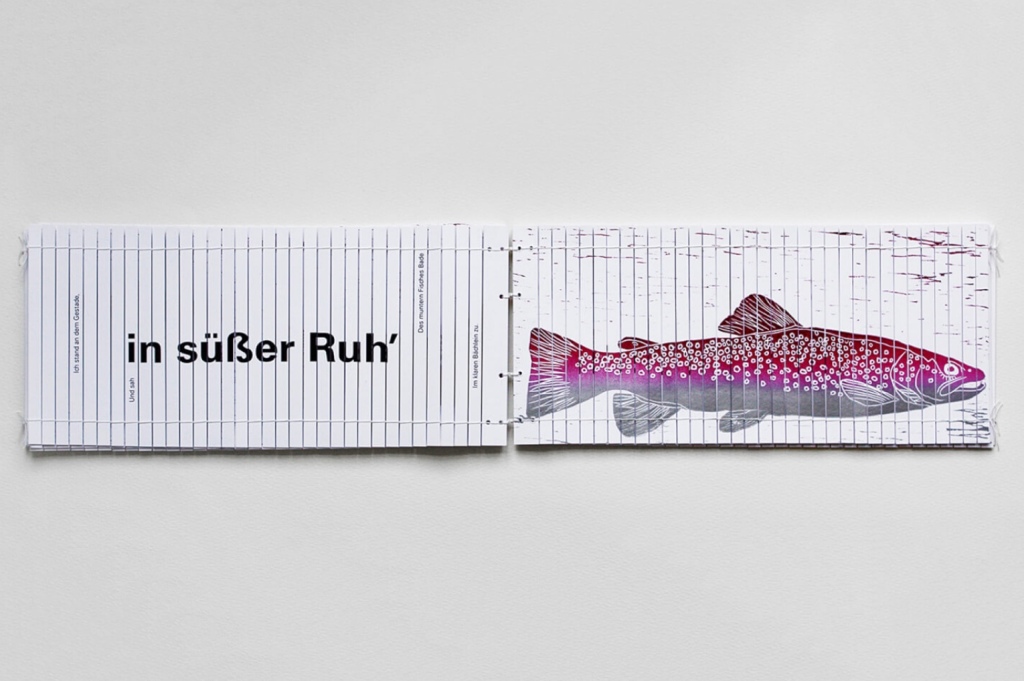

Here is an example I saw in a church in Muenster, Germany, in 2015. The page is open to the Beatitudes: